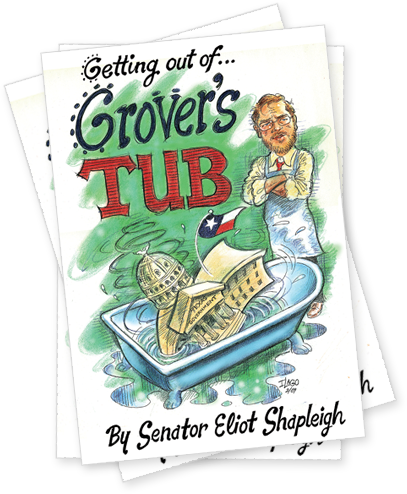

Getting Out of Grover's Tub

Chapter 8: Government by Lawsuit

“Just say no.” That was Nancy Reagan’s slogan all though the 1980s in her fight against drugs. Today, it’s the mantra of Texas’ Republican Party. What it means in Texas, due to flat refusal to solve problems, is that more and more agencies are run by lawsuit. Here’s how that works.

The Department of Justice (DOJ) began a civil rights investigation of Texas’ state schools for the mentally retarded in early 2005. What started out as an investigation of one state school for abuses by direct care staff has broadened, first to another state school, then the entire system.

After the Lubbock investigation, the DOJ found that Lubbock “substantially departed from generally accepted professional standards of care in its failure to: protect residents from harm; provide adequate behavioral services; provide freedom from unnecessary or inappropriate restraints; provide adequate habilitation; provide adequate medical care (including psychiatric services, general medical care, pharmacy services, dental care, occupation and physical therapy, and physical and nutritional management); and provide services in the most integrated setting appropriate to their needs.”

On December 1, 2008, the DOJ concluded that “numerous conditions and practices at the Facilities violate the constitutional and federal statutory rights of residents. In particular, … the Facilities fail to provide consumers with adequate: (A) protection from harm; (B) training and associated behavioral and mental health services; © health care, including nutritional and physical management; (D) integrated supports and services and planning; and (E) discharge planning and placement in the most integrated setting.”

The DOJ’s most recent letter signifies that the serious problems found initially at the Lubbock State School were not unique to one state school and indicative of systemic issues. The DOJ attributes these systemic issues to high staff attrition and vacancy rates for direct care staff and clinical professionals. Until the state can successfully retain, train and supervise their staff, we can not begin to address the problems and deficiencies identified by the DOJ.

“It was just horseplay.”

That’s what the Department of Aging and Disability Services (DADS) told state Rep. Abel Herrero, who represents the district in which the Corpus Christi State School is located, two months ago when cell phone videos surfaced that showed employees encouraging residents with mental disabilities to fight each other.

“I was disappointed that the agency solely responsible for the care of persons in state school settings would not be willing to recognize the severity of the situation,” said Herrero. The Representative described the behavior in the videos as “despicable, deplorable, completely unacceptable.”

“The state schools have been systematically starved of resources,” I was quoted as telling the Dallas Morning News. “What we have now is so little supervision that staff are pitting residents against one another like human cockfights.”

This “fight club” brought national attention to the dire situation of our state school system. CNN has reported on this issue on March 10, 2009 and several videos of these fights have been released to the public.

On May 12, 2009, Texas’ senior U.S. Senator Kay Bailey Hutchison spokesperson Rick Wiley stated “[t]he fight clubs that took place at one of Texas’ state schools are a sad chapter in Texas history and further proof of Rick Perry’s failed leadership as governor of this state.” He goes on to contend that Perry knew the DOJ was investigating allegations of abuse in state schools more than four years ago—and has done little since. “Since then, the problem has only gotten worse and Perry has done nothing to address it,” Wiley said. “All Texans deserve better than this appalling failure of leadership, but specifically those who are the most vulnerable among us.”

As members of the legislature, we have a fundamental duty to provide legislative and fiscal oversight over the operations of our state agencies—especially over those entrusted to care for our most vulnerable citizens. The Texas Legislature must adequately fund the state school system. Last session, in response to the DOJ’s findings regarding the Lubbock State School, we fought to fund $49 million to hire almost 1,700 new employees for the facilities. It was a start, but not a solution to the significant problems in the system. This session, over a year after the DOJ expanded their investigation to include every single state school in Texas, DADS reached a settlement with the DOJ and asked for and received an additional $48 million during the next biennium to meet the various stipulations of the settlement with the DOJ. Why does it take a lawsuit to solve problems in Texas?

Bilingual education is another arena where lawsuits are forcing the state to act. Recently, a Federal Judge ruled that Texas failed to overcome language barriers for tens of thousands of Latino students in secondary programs. In the ruling, the Court said that “[a]fter a quarter century of sputtering implementation, Defendants have failed to achieve results [and]…failed implementation cannot prolong the existence of a failed program in perpetuity.”

Frew v. Hawkins, a Medicaid class action lawsuit against the state of Texas, was filed in 1996. The plaintiffs sued the state for failing to provide adequate health care for children enrolled in Medicaid. The charges included poor screening, case management and outreach. Despite what seemed like an early resolution of the case with the state of Texas agreeing to improve children’s access to and awareness of the Medicaid Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment program, the state didn’t honor the consent decree and years of litigation followed.

Although the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of the plaintiffs in 2000, the state persisted in its efforts, claiming that the consent decree could not be enforced because the state could not be sued. In early 2007, the case culminated when the U.S. Supreme Court declined to review the case again. As a consequence, the state of Texas entered into a corrective action plan with the plaintiffs. The Legislature in 2007 had to provide significant increases in reimbursement rates for doctors and dentists (25 percent and 50 percent, respectively) as well as set aside $150 million each biennium for strategic initiatives intended to provide better, comprehensive health care to Medicaid children. However, given that the state has only spent $33 million of the $150 million this biennium, the state might very well be in court again for failure to meet the requirements of the corrective action plan.

What’s going on here? Voters ought to ask is why does it take lawsuits to solve problems in Austin?