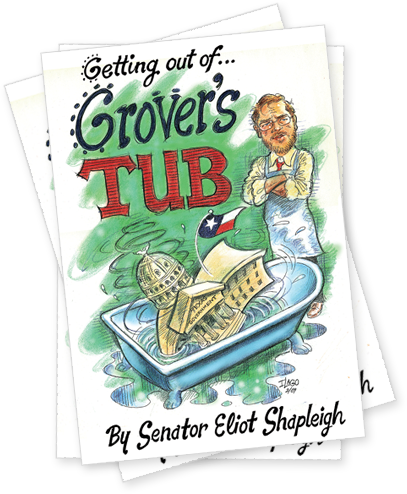

Getting Out of Grover's Tub

Chapter 16: Grover’s Lists

Twelve years. Eight years. That’s how long 39-year old Ricky Broussard and 19-year old Joel Johnson waited to receive independent living services and community living assistance and support services from the state.

It’s ten years and counting for Juliana Aguilar, a 15-year old who waits to receive short-term care services like assistance with bathing, dressing and transportation to and from doctors’ visits. Although she qualifies for these state services, her parents continue to struggle by working four jobs between the two of them to cover their family’s household expenses and doctors’ bills—that’s their reality.

For Vicki Schilling, her 44-year old sister Janis has been on a waiting list for almost a decade, since their mother—and Janis’ caretaker—passed away. Every day, she struggles to balance the needs of her sister, who is mentally retarded and prone to violent temper tantrums, with those of her 8-yr old son and her 87-year old father. And although she does not want to institutionalize her sister, she has begun to consider it as an option. The irony is that if she puts her sister in an institution for a while, her sister will then be entitled to home and/or community-based care—without having to wait on the interest list!

Across these pages, we have detailed how Norquist’s philosophy has touched every Texan. Norquist is the one who famously said, “[m]y goal is to cut government in half in twenty five years, to get it down to the size where we can drown it in the bathtub.” Far too many Texans—who desperately need quality health care—are now in Grover’s tub.

For programs providing community services for the disabled, more than 85,000 wait on interest lists. In many key programs, more Texans wait for services on interest lists than are actually being served. For example, in the HCS waiver program, which provides home and community-based services as an alternative to institutionalization for those who are mentally retarded, 33,436 get served while 39,455 wait for services.

28,023 wait for services from the Community Based Alternatives program, which provides home- and community-based services to people who are elderly and to adults with disabilities as a cost-effective alternative to living in a nursing home.

24,126 for services from the Community Living Assistance and Support Services (CLASS) program, which provides home- and community-based services to people with related conditions as a cost-effective alternative to placement in an intermediate care facility for persons with mental retardation or a related condition.

11,584 wait for services through the Medically Dependent Children’s Program (MDCP), which services to support families caring for children who are medically dependent and to encourage de-institutionalization of children in nursing facilities.

Even if the Dept. of Aging and Disability Services (DADS), which is the state agency in charge of administering these programs, receives all of the funds requested for 2010-11, the state will not be able to serve a majority of individuals who need these services. The chart below highlights the number of people who will be served if the proposed budget is funded as passed and the number of people who will still be on the various interest lists:

| Average # of Individuals Served per Month | Average # of Individuals on Interest List per Month | |

|---|---|---|

| HCS | 20,636 | 61,710 |

| CBA | 29,576 | 43,389 |

| CLASS | 6,089 | 48,289 |

| MDCP | 3,029 | 29,123 |

How does this happen? Several years ago, I questioned Thomas Chapmond, who was then Commissioner of the Department of Family and Protective Services, about how many investigators his agency needed to avoid tragic headlines about abused children.

At the time, Chapmond told the Senate Finance Committee that the department’s budget accurately reflected the number of caseworkers needed in the state—even though Texas caseworkers had almost three times the number of cases as the national average.

Two years later, in 2005, when headlines all over the state recounted tragedies like the shooting death of four-month old Brianna Battle — killed a few months after a CPS visit to her and her mother—I asked Mr. Chapmond on the record why he did not ask for enough investigators to do the job right.

“Because I thought I’d be fired,” he replied.

Under government by Grover, agency heads get pressured to keep budgets down and keep real numbers away from lawmakers. In Thomas Chapmond’s case he told the Senators on the Finance Committee a lie to keep his job.

Even today, caseworkers in Texas have the highest caseloads in the United States. In fact, our CPS conservatorship caseworkers’ average caseload is 43.3 — more than twice the national average of 18.9 and almost three times the 15 caseload average recommended by the Child Welfare League of America.

Thomas Chapmond’s lie risked children’s lives. That’s the reality of Grover’s tub—the lives of Texas children are risked so that agency heads can keep their jobs by telling us lies about the true needs of Texans.

So year after year, Texas’ most vulnerable citizens—children, the mentally ill, and the disabled—are left waiting. Texans deserve better.