As nation discusses health care, Texas doctor shortage expected to worsen

September 6, 2009

To understand why Harvey Laas, a rancher with no medical training, runs a health clinic out of a spotless 40-foot truck, it helps to know that his family has worked to bring doctors to the area since shortly after arriving in Waller County in 1896.

Written by Corrie MacLaggan, Austin-American Statesman

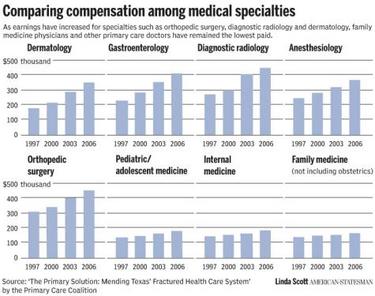

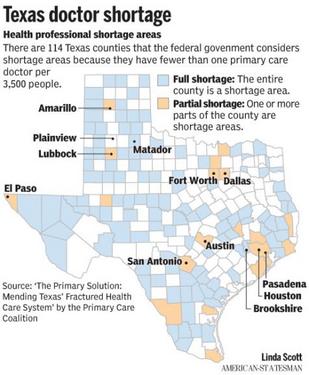

BROOKSHIRE — To understand why Harvey Laas, a rancher with no medical training, runs a health clinic out of a spotless 40-foot truck, it helps to know that his family has worked to bring doctors to the area since shortly after arriving in Waller County in 1896. Today, the family's work is not done. The growing county west of Houston, where Laas and a team of nurses run a community clinic on wheels, has the fewest primary care doctors per capita of any Texas county where a doctor is practicing. There was one doctor for every 14,000 residents as of the state's last count in 2008. "It is, I guess, the family disease," Laas, 52, said of his work to better the community where he expects to spend the rest of his life. As talk on national health care reform centers on providing insurance for everyone, Texas and the nation are already struggling with a shortage of primary care doctors that is expected to keep growing. In Texas, 114 of the 254 counties have been designated by the federal government as primary-care shortage areas. Some clinics spend months trying to lure doctors, and some patients drive one or two counties away for even the most routine health care. Tom Banning, CEO of the Texas Academy of Family Physicians, said that the number of primary-care doctors the state produces hasn't kept pace with its birth rate and the influx of residents from other states. Nationally, there are 81 primary-care doctors for every 100,000 people; in Texas, the average is 68. "There aren't enough doctors currently practicing in Texas to care for the folks we have, much less the uninsured," Banning said. Texas has the nation's highest rate of uninsured — one in four. And the problem is expected to get worse, as doctors age and retire and medical students continue to choose specialties that pay more than family medicine or internal medicine. Proposed national health care reforms would change how Medicare — and therefore private insurers — pays doctors, increasing payments to those who provide primary care. Banning said that would encourage medical students to choose primary care, which could help alleviate the shortage. This year, Texas lawmakers tried to address the doctor shortage by enhancing the state's medical school loan repayment program to encourage doctors to practice in underserved areas.The changes increase the amount of money available to each doctor from $45,000 over five years to $160,000 over four years.And money from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act is going toward expanding a similar federal program that has far more applicants than spots.

Texas' 2003 reforms limiting medical liability have brought a significant number of primary care doctors to Texas, but getting them to rural areas remains a problem, said Jon Opelt, executive director for Texas Alliance for Patient Access.

There are 27 Texas counties that have no doctor at all, including Motley County in the Panhandle. In Matador, residents packed a town hall meeting on health care last fall. They weren't talking about national health care reform efforts, but about how to cope with the loss of the physicians assistant at the town's only clinic.

The doctor shortage also extends to some urban areas. In Pasadena, just outside of Houston, one clinic searched for a primary care physician for eight months before finding a doctor willing to practice alone in the clinic.

Filling the need

Waller County has been trying to lure doctors since at least the early 1900s, when Laas' great-grandfather wrote to Tulane University medical school and what is now the University of Texas Medical Branch, offering a place to live if a doctor would come to the county. A Dr. Stewart accepted the offer, and made such an impression that Laas's father — and, later, Laas and his son — got the middle name Stewart.

Later, Laas' great-grandfather joined other residents in paying for the medical school education of a local man who later returned to practice in the county.

In 1985, Waller County's only hospital closed, which has hurt the county's ability to attract doctors, Laas said.

Laas, a father of two who is married to a nurse, started his clinic in December 1993. The clinic, which provides care to both insured and uninsured patients, is now part of the Fort Bend Family Health Center Inc.

When he isn't managing his cow-calf operation, Laas runs the mobile clinic, which doesn't currently travel to different locations. Some days, he's the setup man — moving traffic cones, folding down the steps and hooking up the truck to electricity and the Internet (for electronic medical records) at the United Way building.

Inside, there are two examining rooms.

"This is our baby," Laas said. "It's obviously cramped, but we can see more than 20 patients a day. We can do everything here you can do at a doctor's office."

But there are no doctors. On a recent afternoon, family nurse practitioner Mary Ann Neeley and licensed vocational nurse Olivia Morales took care of patients, many of whom had appointments for back-to-school immunizations. If necessary, Neeley can refer patients to doctors in Richmond, 25 miles away. But it's easier to find a doctor's office to send people with insurance, Laas said.

"People who suffer most in this county are the uninsured working poor," Laas said.

Patient Teresa Villanueva, 60, came to the clinic because of neck pain. Her family's income comes from her husband's job as a maintenance worker at a home for people with disabilities, and the couple does not have health insurance, she said. Villanueva said she came to the clinic from her home 30 minutes away in Bellville, bypassing a pricier clinic in Sealy. The Brookshire clinic charges on a sliding scale according to income, and Villanueva pays $40 for a visit.

At night, a clinic staffer parks the truck at the safest place possible: the nearby police station. Laas hopes to build a freestanding clinic near the United Way building in Brookshire.

Searching far and wide

During the eight months Pasadena Health Center was searching for a doctor, there was one thing that kept scaring off potential applicants.

If they took the job, they'd be the clinic's only physician. Nobody would be around to take over if they were sick or on vacation.

"They'd run out the door as fast as they came in," Chief Executive Officer John Sweitzer said.

It's a struggle that the city just southeast of Houston shares with rural clinics in the Texas Panhandle and in border communities. The Pasadena clinic, which is on the bottom floor of a brown office building, has the added challenge of going after some of the same doctors being recruited by Houston's gleaming, world-class medical facilities less than 20 miles away.

After interviewing 15 people, Sweitzer last year hired Dr. Suchmor Thomas, who came to Pasadena from Lone Star Family Health Center in Conroe.

Like a quarter of Texas doctors, Thomas graduated from a foreign medical school — in his case, T.D. Medical College in Kerala, India. In 2008, 37.9 percent of first-year participants in residency programs that could lead to primary care were graduates of foreign medical schools, according to the American Academy of Family Physicians.

Thomas said he likes working at the clinic because its patients often have nowhere else to go. But he knows that he has to come to work unless he's really sick.

José Camacho, executive director of the Texas Association of Community Healthcare Centers, said that's a dilemma common around the state, especially rural areas where doctors might be the only physician in a 40-mile radius.

"If you're the only doctor to the area, if you want to play golf, who replaces you?" asked Camacho, whose member clinics serve the uninsured and underserved. "Not that there's golf courses."

Dr. John Zerwas, a Republican state representative from Richmond, said that although pockets of urban areas might have fewer doctors, that might not signify a shortage.

"If you look at how close they are to Houston, you have to ask yourself: 'Is that region really underserved?' " said Zerwas, who is an anesthesiologist.

But Banning said that even if residents of an underserved area are getting care somewhere, that doesn't mean it's the right care at the right time and price.

"Why shouldn't they have a physician in their community to care for them?" Banning asked.

Feeling the loss

Motley County, which doesn't have a Dairy Queen, also doesn't have any doctors practicing.

It's a farming and ranching county of about 1,300 people located a 90-minute drive northeast of Lubbock. Until last year, residents could visit Motley County Clinic, which is on Main Street in Matador and was staffed by a physician assistant. The clinic hasn't operated since last year, when the physician assistant left for a job in a neighboring county.

The clinic was run by Regence Health Network, which has several Panhandle clinics. Regence couldn't find another medical provider to go to rural Matador, said Cynthia Wetzel, Regence's chief nursing officer.

"It's an awesome place," Wetzel said. "It's got rolling hills, neat little crevice-looking canyon things and mesquite trees. It's definitely a cowboy setting."

But, she said, "a lot of people aren't looking to live where there's no movie theaters, a limited number of churches, no choices in schools."

Motley County Judge Ed D. Smith said the loss of the clinic "had a terrible impact on us."

Last September, Regence held a town hall meeting in Matador on the future of the clinic.

The meeting was to be held at the library annex, but so many people showed up that it was moved to a Baptist church, Smith said.

"We all moved over there and pretty well filled the place up," Smith said. "It was a very highly emotional, angry type of situation."

Regence considered offering telemedicine — consultations by phone and video conferencing — but ultimately pulled out of the county completely, Wetzel said.

The county is looking at options for the clinic's future. Meanwhile, residents such as Dianne Washington and her soon-to-be 89-year-old mother, Jo Scott, seek health care in places like Crosbyton (about 45 miles by car from Matador), Paducah (30 miles) and Plainview (60 miles).

"Now it's a major half-day production," Washington said. "You don't want your 89-year-old mother driving to Plainview to have her blood checked by herself."

![]()

Fair Use Notice

This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a "fair use" of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond "fair use", you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.