Getting Out of Grover's Tub

Chapter 9: Captured and Corrupted at TCEQ

We all like to think of Texas as a place of natural beauty—from the plains of Amarillo to the ranches of West Texas, from the Texas coast to the Hill Country. We also like to think of ourselves as hardy and healthy a people as Pecos Bill tackling a tornado.

If that’s so, then why is Texas’ environmental commission putting our land and our lungs at risk? Why is TCEQ a lapdog for the nation’s largest polluters—and why does Texas have the nation’s worst environmental record?

Here are the facts when it comes to Texas air and water.

More than any other state in America, almost twenty-four million Texans now live with the highest levels of volatile organic compounds, toxic chemicals in our water, and carcinogens and carbon dioxide in our air.

In terms of ozone pollution, Houston and Dallas are now the fourth and seventh worst cities in the United States, respectively. If Texas were a nation, it would rank seventh in the world in total carbon dioxide emissions.

So, what happened?

A key advisor to Texas leaders, Grover Norquist, famously set the low bar for government service. He said his goal was to get government “down to the size where we can drown it in the bathtub."

Norquist’s core belief is that government is the enemy. His hostility to basic and responsible governance now runs Texas.

More than anything, Norquist’s philosophy explains why Texas is now the nation’s number one polluter—and why TCEQ is active in promoting the agenda of the nation’s worst polluters. In an era where deregulation cost taxpayers millions of dollars in bailouts, Norquist’s philosophy deserves serious scrutiny. If you want to know what “deregulated” air tastes like, take a deep breath.

Out here in El Paso, we’ve seen TCEQ’s lack of effort first hand.

Since 1887, our central city had been dominated by a smelter owned by ASARCO For over a century, ASARCO emitted thousands of tons of lead, arsenic, and sulfur dioxide into the bi-national airshed of El Paso and Juarez. You may have seen ASARCO’s towering 828 foot smokestack as you rounded the bend on I-10 near UTEP. In 1999, when copper prices dropped to historic lows of only 60 cents per pound, ASARCO mothballed the smelter. A few years later when copper prices went up, ASARCO applied once again to put more than 7,000 tons of pollutants into El Paso’s air each year. Under its new permit, the ASARCO smelter could potentially have the distinction of being the facility with the highest level of lead emissions in the entire country.

With similar ASARCO operations spread throughout the American West, this company’s pollution has resulted in billions of dollars in clean-up costs in towns from Tacoma to East Helena to Omaha.

By 2007, 955 properties had been cleaned of lead and arsenic in El Paso—with potentially hundreds more undiscovered. Back in the early 1970s, groundbreaking research by the Centers for Disease Control, right here in El Paso, demonstrated that lead can harm a child for life, including lower IQ levels. To shed billions of dollars of health and environmental clean-up obligations, ASARCO filed Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 2005, leaving 75 communities in 16 states environmental clean-up claims totaling $11 billion.

It was the largest environmental bankruptcy in U.S. history. Yet ASARCO continued to fight to be able to pollute El Paso’s air.

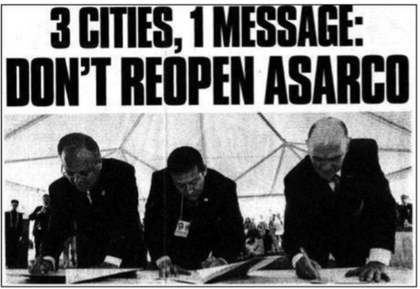

Throughout the renewal process, the City of El Paso contested ASARCO’s air permit. Both the Governors of New Mexico and Chihuahua joined the citizens of El Paso asking that ASARCO’s massive air permit be stopped. In an historic joint City Council meeting right on the Texas, New Mexico, and Chihuahua line, Mayors of El Paso, Juarez, and Sunland Park signed a joint resolution asking that our people be protected from further pollution.

In February 2008, the three TCEQ Commissioners finally considered ASARCO’s air permit renewal application. Hundreds of El Pasoans traveled to Austin to voice their opposition to the potential reopening of ASARCO’s smelter. After oral arguments, however, all three Commissioners voted to approve the air permit renewal.

ASARCO was represented by the law firm Baker Botts at the hearing. A little over a month later, records from the bills filed by Baker Botts in ASARCO’s bankruptcy revealed that attorneys and lobbyists for Baker Botts had been meeting secretly with TCEQ Commissioners throughout the hearing process. In a $10.8 million sworn fee application, Baker Botts told the bankruptcy court that their attorneys had engaged in the following during the hearing process:

- “Preparation and participation in a meeting with TCEQ Commissioner and Legislative Assistant; discussed setting of permit hearing, air quality monitoring and reaction to plant re-opening…”, and

- “Preparation and participation in an event for the Senate Hispanic Caucus; discussed TCEQ agenda for ASARCO permit with Chairman Garcia…”

In light of this information, I filed two public information request with TCEQ after its commissioners approved ASARCO’s air permit on February 14, 2008 and February 18, 2008 asking for key documents, emails, and cell phone records. The requests were made under the ‘legislative purpose’ statute, which allows legislators to gain access to otherwise confidential information, provided that it is for a legislative use.

Rather than turning over the documents, upon receiving my request, instead of releasing the materials, TCEQ submitted an 18 page letter to Texas Attorney General Greg Abbott (AG) on March 4, 2008, arguing that I should not be given access to confidential information. On May 16, 2008, however, the AG disagreed with TCEQ and said I was entitled to all requested materials. In a further attempt to deny access to the documents, TCEQ filed suit in May 29, 2008 to challenge the AG’s ruling and continue to withhold documents.

In April 2009, a Texas District Court Judge ruled that TCEQ could not deny the request. Still, rather than turning over the documents, the commission appealed again- hiding the documents with further delays.

Disgusting? Yes. Surprising? No.

This tale of secret meetings and the capture and corruption of TCEQ is a story that resonates across Texas. When the EPA recently tightened the federal limit on ozone in smoggy areas like Houston and Dallas, TCEQ repeatedly urged the EPA to maintain the status quo.

Fortunately, despite TCEQ’s best efforts to deliver a gift wrapped air permit, ASARCO, announced in February its decision to end attempts to reopen the smelter It turns out that the EPA did not buy ASARCO and TCEQ’s argument that renewing a ‘grandfathered’ permit was legal. Citing the fact that significant portions of the plant were only good for scrap metal, the EPA was going to require ASARCO to begin the permit process again. This caused the company to throw in the towel for good and request their air permits be voided immediately.

Beyond El Paso, the commission has a history of disregarding public input on permits it awards and of disregarding scientific opinion on permits.

In April 2009, TCEQ granted a 10-year renewal of Dallas-based TXI’s cement kilns in Midlothian – despite outcries from residents who blame it for increased pollution in North Texas. About 200 people urged commission to hold a public hearing, but their requests fell on deaf ears.

In the summer of 2008, the TCEQ permitted two licenses to Waste Control Specialists to bury millions of cubic feet of radioactive waste in West Texas. After a four-year review, the commission’s own technical staff recommended denying the permit, citing that the permit could not legally be granted because of its proximity to two aquifers and almost certain irradiation of groundwater.

Rather than take those recommendations, the commission’s executive director, Glenn Shankle overruled them. This allowed for permits that would earn Waste Control millions of dollars- and led to three of Shankle’s staff quitting the commission in protest.

Records show that Shankle was frequently meeting with Waste Control officials, attorneys and lobbyists during their permit application. Six months after stepping down at the agency, Shankle was working for Waste Control Specialists – the company he was previously supposed to be regulating. His contract as a lobbyist for them is estimated to be worth between $100,000 and $150,000 a year.

Given the reality of a failed TCEQ, Houston Mayor Bill White has long pushed for local solutions to pollution. Mayor White expanded a city ordinance that requires local businesses to pay registration fees based on the number and type of air pollution sources located on the businesses’ properties. An industry group filed suit to prevent the law from being enforced, and TCEQ, despite not being part of the lawsuit, willingly and actively sided with polluters in a letter to the judge.

Rather than regulate polluters, the TCEQ is at their beck and call.

As Mayor White put it, “I think that something strange is going on when the polluters can contact the agency that is supposed to be regulating pollution and the polluters can get the state agency to try to be on their side.”

Why is this happening? Because a philosophy dedicated to destroying government has run government for nearly a decade. Public officials charged with the duty of protection have failed to protect.

Instead, they have participated in “drowning” effective governance and putting us all in Grover’s tub. Thomas Jefferson taught us that it is “the people to whom all authority belongs.”

Isn’t it time that the people take back authority over the quality of air they breathe? Do Texans really deserve the nation’s dirtiest air?