Getting Out of Grover's Tub

Chapter 14: Grover's Trifecta

“We just don’t have enough money, basically, to provide a quality education experience to our students.”

That quote from La Vega ISD superintendent Sharon Shields exemplifies what is happening across public education in Texas: the collision of consistent underfunding, increased mandates, and rising costs have resulted in a budgetary nightmare for public schools. The end result is an education system that is less able to respond to the needs of its students and provide a 21st Century learning experience.

Catherine Clark, associate executive director of the Texas Association of School Boards, put it this way: “There’s going to be loud conversation this fall and real screaming in 2009 unless there is real relief. Or one by one, we’re going to be toppling over the edge of the cliff.”

Fort Worth and Arlington school districts are two of many statewide forced to shift millions of dollars from their savings accounts to cover budget shortfalls. Fort Worth alone will spend about $43 million more than it brings in during the 2008-09 school year, forcing the chief financial officer to admit, “All we have are hard choices and not many options.”

Wayne Pierce, executive director of the Texas Equity Center, sums it all up: “We’ve reached a point where the wealthy districts have dropped below what they need and the property-poor are scraping the bottom.”

During our Grover’s Tub series, we have highlighted the results of years of living under the reign of those who value tax cuts for the wealthy over good schools for kids. Grover Norquist, the national leader of the anti-government movement, once famously said, “My goal is to cut government in half in twenty-five years…to get it down to the size where we can drown it in the bathtub.” The futures of our children, however, are now in Grover’s tub, too, and deliberate underfunding places those futures at risk.

Public school finance has always been a major issue facing Texas. But within the school finance debate, there has been the question of how to ensure that all Texas children are well-educated while funding that education mainly through a local property tax. Because property wealth is not evenly distributed across the state, some school districts have the advantage of taxing a larger tax base than others. This has led to some school districts being able to provide a more comprehensive and rigorous education for their students than others. As a result, a series of legal challenges were raised against the state’s school finance system to force the state to provide more equitable public school funding.

In 2001, both property-wealthy and property-poor school districts sued the state, arguing that they were forced to adopt higher tax rates in order to meet state requirements and therefore the local property tax had become an unconstitutional statewide property tax.

The Legislature eventually changed public education finance in the summer of 2006, but that change is now proving to be less than successful. At the behest Rick Perry and Tom Craddick, the Legislature packaged together a compressed local property tax rate and shifted taxes to a new business income tax, a motor vehicle tax and an increased cigarette tax. Despite rising construction and energy costs and the need for more certified teachers, the Republican plan also required all future revenues from the taxes to be dedicated to property tax relief, not public education, thus resulting in a structural budget deficit estimated to be $5.8 billion by 2010-11.

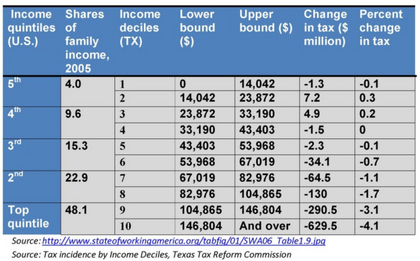

The initial Republican plan cut taxes by $920 million for everyone making more than $104,000 and hiked taxes by $10.8 million on everyone making less than $33,000, a classic example of the Grover Norquist philosophy: tax cuts for the wealthy, tax shifts to the middle class and programs too poor to work well.

Here is a side-by-side chart showing wealth levels and tax cuts:

Under the final 2006 revisions, any increase in local property value goes to reducing the amount the state must pay by a corresponding amount. As a result, school districts find their hands tied once again, unable to raise sufficient revenue to pay for rising costs. Huge spikes in energy, transportation and food costs have left districts without anywhere to turn. Recently, at a Senate Finance hearing, an influential East Texas senator stated, “I think the overall school finance plan is not working. I think we have a new business tax, we have not seen property tax relief and, on top of that, we’ve now tied the hands of public schools in terms of ability to raise revenue … we now have the trifecta disaster.”

That indeed has been the result. After years of lawsuits and four special sessions of the Legislature, the result is Grover’s Trifecta: a tax shift that hiked business taxes, shifted net taxes away from the wealthy and starved Texas public schools to the point where many are now using reserves to pay day-to-day bills.

During the 81st Legislative Session, the Texas Legislature responded with H.B. 3646, a stop gap measure using $3.2 billion of stimulus money to return to a formula-driven public school finance system that improves equity, reduces recapture, and provides increases in educator salaries. But more work remains, as Sen. Florence Shapiro (R-Plano) admitted at session’s end, “[t]his was not the session to fix the problems in our school finance system."

Twenty-five years after Rick Perry brought government by Grover to Texas, where do we rank relative to the other states in America?

We are first in dropouts and 46th in SATs. Our teachers are near last in pay. Fewer Texans hold high school degrees than citizens in any other state.

In Texas, we have a choice to make. We can continue to travel down the path toward Grover’s tub, valuing tax cuts for the wealthy over good schools for our children, shifting taxes from the wealthy to the middle class and steadfastly refusing to fund public education properly. Or we can make the investments that we need to succeed.

The former state demographer and current head of the U.S. Census Bureau, Dr. Steve Murdock, warned about remaining on the same path Texas is on: “If the current relationships between minority status and educational attainment, occupations of employment, and wage and salary income do not change in the future from those existing in 1990, the future workforce of Texas will be less educated, more likely to be employed in lower-level state occupations, and earning lower wages and salaries than the present workforce.” Dr. Murdock also predicted that if current trends continue, in about 30 years, average household incomes will be $6,000 less than they were in 2000.

So Texas’ future is here now—tax cuts or kids? What will it be?